“No fear could make me late for filming. I was never late, no matter how much I drank the night before.”

TOSHIRŌ MIFUNE

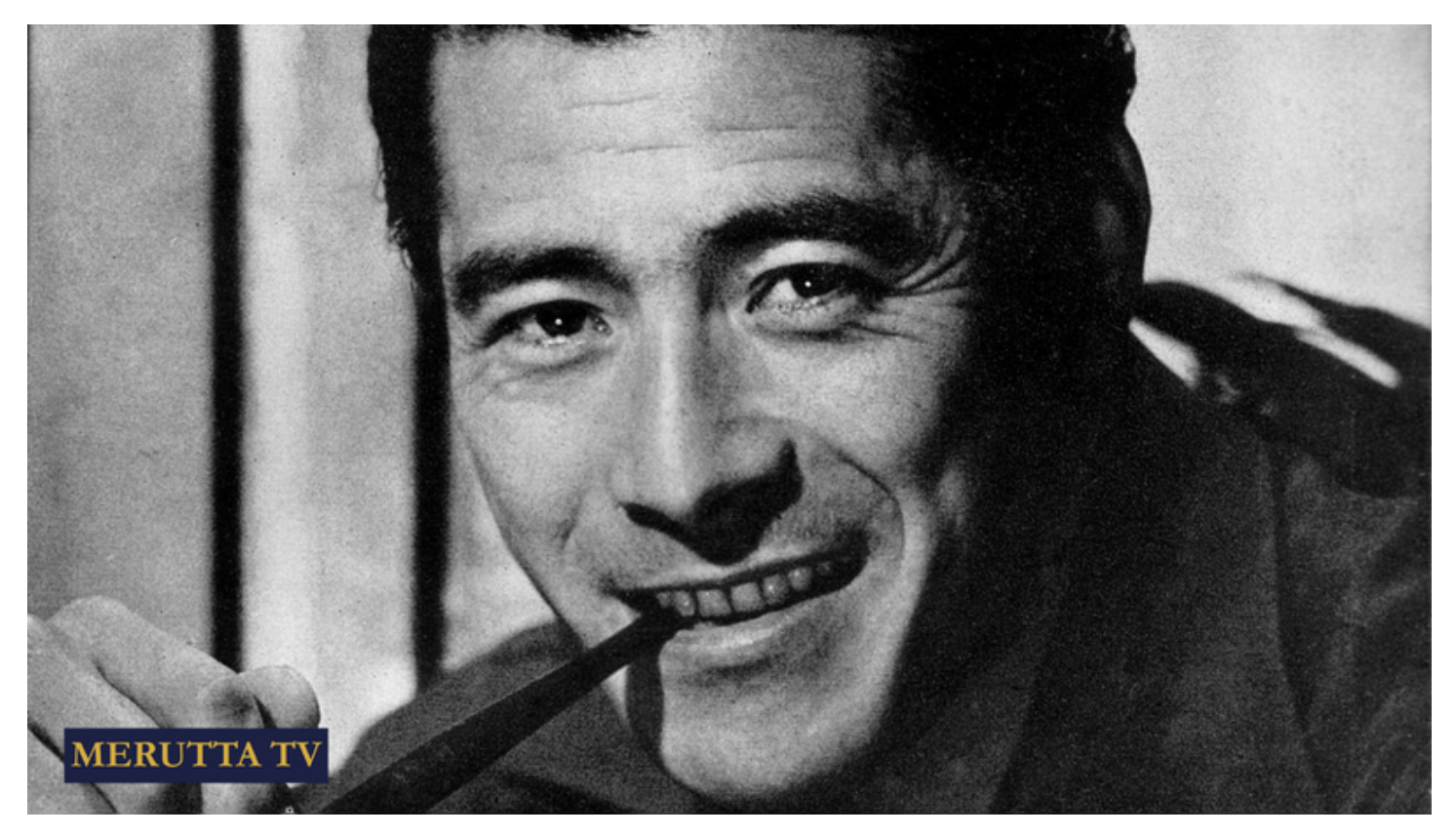

Toshiro Mifune (1920–1997) stands as one of the most towering figures in the history of world cinema. Few actors have so deeply and enduringly embodied the image of their nation on screen as he did. For more than four decades, Mifune personified the ideals, contradictions, and transformations of Japanese identity in the 20th century — not merely as an actor but as a cultural phenomenon. His on-screen presence, both volcanic and restrained, became synonymous with Japanese masculinity and dignity. Mifune was not simply a performer — he was a symbol of an era when cinema sought truth, and acting became a form of philosophy.

Toshiro Mifune was born on April 1, 1920, in Qingdao (Tsingtao), China, then under Japanese control. His parents, both Japanese, ran a photographic studio — his father as a photographer and his mother assisting in the business. From early childhood, he was known for his independence and defiance, qualities that would later define his screen personas. During World War II, Mifune served in the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service, specializing in aerial photography. This experience profoundly shaped his worldview, deepening his understanding of human fragility amid historical cataclysms. Although he rarely spoke publicly about Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he once remarked: “The shadow they cast is longer than any sword I ever wielded on screen,” a poetic reflection on the intersection of violence, memory, and humanity.

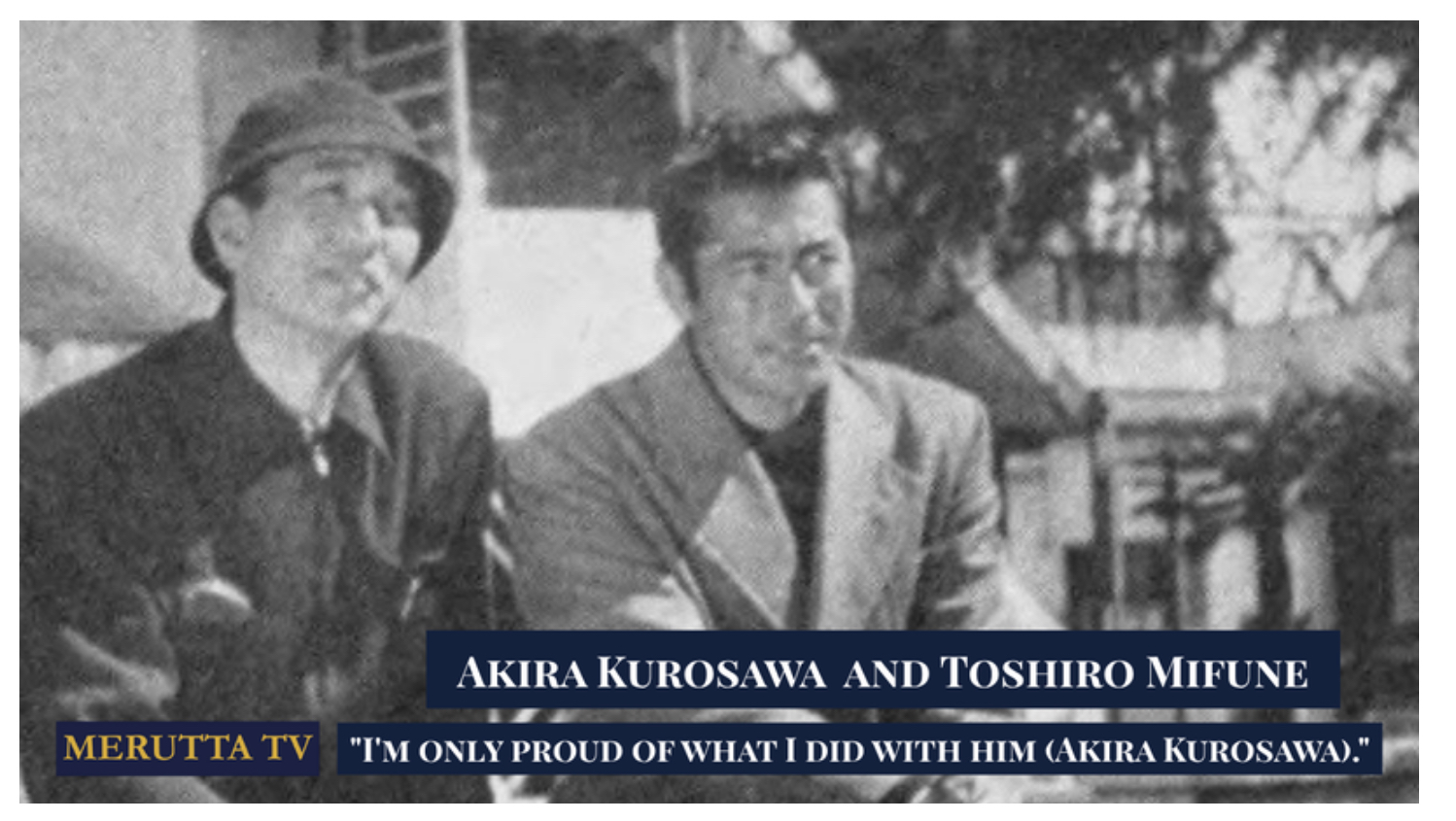

After Japan’s surrender, Mifune returned to a devastated country. Seeking work, he joined Toho Studios, initially as a camera assistant, but his striking appearance and intense energy quickly drew the attention of directors. By the late 1940s, his talent had become undeniable. His breakthrough came with Akira Kurosawa’s “Drunken Angel” (1948), marking the beginning of one of cinema’s most fruitful collaborations. Kurosawa, who later described Mifune as “a hurricane of talent,” immediately recognized his unique ability to express raw energy and emotional complexity without words. Over the next 17 years, they made 16 films together — all of them now regarded as classics of world cinema.

Mifune’s partnership with Kurosawa was more than a professional alliance — it was an act of mutual discovery. Their collaborations — “Rashomon” (1950), “Seven Samurai” (1954), “Throne of Blood” (1957), “Yojimbo” (1961), and “Red Beard” (1965) — redefined Japan’s place in global cinema. Mifune’s performances oscillated between primal force and philosophical depth, with his characters often torn between personal conscience and social duty. Kurosawa said: “When Mifune enters a room, the atmosphere changes. When he is silent, the silence itself becomes tangible.” His acting technique — physical, instinctive, deeply human — became a model for future generations. Unlike the stylized kabuki tradition, Mifune brought a new naturalism to Japanese cinema, grounded not in formal gestures but in inner emotion and bodily expression.

After parting ways with Kurosawa in 1965, Mifune continued to broaden his artistic horizons. He worked with acclaimed directors in Japan and abroad, including Hiroshi Inagaki (“Samurai Trilogy,” 1954–1956), Masaki Kobayashi (“Samurai Rebellion,” 1967), Terence Young (“Red Sun,” 1971), and Steven Spielberg (“1941,” 1979). His commanding presence transcended language barriers, making him one of the first Japanese actors to achieve global stardom. His work introduced Western audiences to Japanese cinema as an art form rich in dignity, nuance, and philosophy.

After parting ways with Kurosawa in 1965, Mifune continued to broaden his artistic horizons. He worked with acclaimed directors in Japan and abroad, including Hiroshi Inagaki (“Samurai Trilogy,” 1954–1956), Masaki Kobayashi (“Samurai Rebellion,” 1967), Terence Young (“Red Sun,” 1971), and Steven Spielberg (“1941,” 1979). His commanding presence transcended language barriers, making him one of the first Japanese actors to achieve global stardom. His work introduced Western audiences to Japanese cinema as an art form rich in dignity, nuance, and philosophy.

In postwar Japan, Mifune was more than a movie star — he was a mirror of national consciousness. His portrayals of samurai, ronin, and morally conflicted men resonated deeply with a society grappling with defeat, reconstruction, and modernization. Critics called him “the soul of bushido” — not as a relic of the past, but as a living embodiment of honor and inner strength.

Despite occasional controversies — such as his outspoken disdain for unprofessionalism or his willingness to abandon projects he deemed unworthy — Mifune commanded immense respect within the industry. In 1986, the Japanese government awarded him the Order of the Sacred @Treasure (Third Class) for his cultural contributions. In 2016, nearly two decades after his death, he was posthumously honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame — a rare accolade for a non-Western actor.

In his personal life, Mifune was known for discipline, loyalty, and restraint. In 1950, he married former actress Sachiko Yoshimine, with whom he had two sons — Shiro and Toshio — and a daughter. His son Shiro continues his father’s legacy through the Toshiro Mifune Foundation and Mifune Production, which preserves his work and organizes retrospectives. Although Mifune rarely spoke publicly about politics, his art itself was a political statement — an affirmation of human dignity amid suffering and change. He once said: “An actor must show the truth of a man. Not the myth, not the legend — the man.”

In his personal life, Mifune was known for discipline, loyalty, and restraint. In 1950, he married former actress Sachiko Yoshimine, with whom he had two sons — Shiro and Toshio — and a daughter. His son Shiro continues his father’s legacy through the Toshiro Mifune Foundation and Mifune Production, which preserves his work and organizes retrospectives. Although Mifune rarely spoke publicly about politics, his art itself was a political statement — an affirmation of human dignity amid suffering and change. He once said: “An actor must show the truth of a man. Not the myth, not the legend — the man.”

Toshiro Mifune died on December 24, 1997, in Tokyo, leaving behind more than 170 roles and a legacy that continues to shape global cinema. His influence can be seen not only in the work of Japanese actors such as Ken Watanabe and Hiroyuki Sanada but also in Western performers, from Clint Eastwood to Daniel Day-Lewis. He was more than an actor — he was a cultural ambassador, a living voice of Japanese cinema in an era searching for its new identity.

His art fused primal emotion with philosophical depth, tradition with modernity, and the Japanese spirit with universal human truth. “Without Mifune, I could not have made my best films,” Kurosawa said. Through his uncompromising honesty, high standards, and deeply human essence, Toshiro Mifune gave Japan a face — and the world a soul — in the language of cinema.

DISCOVER MORE STORIES BY MERUTTA ON MEDIUM