OA new UK-France “one-for-one” migration deal promises to curb illegal Channel crossings — but with only 50 returns a week, experts say it’s more political theatre than real solution.

“This is a pull factor and could increase pressure on the French coast, while local authorities were not even informed!” — said the mayor of Calais, Natacha Bouchart. And the very next day, Emmanuel Macron said at a press conference: “This agreement will have a deterrent effect.” With all due respect to Emmanuel Macron, I think as a politician on this issue he is far too weak.

A deterrent effect? When hundreds of people cross the Channel every single day, and the agreement covers only fifty per week? This is not deterrence. This is window-dressing. Words with no real solution behind them. And behind those words lies nothing but helplessness.

Now let us take a closer look at this agreement. France and the United Kingdom signed what they called a “one-for-one” deal. The idea is simple: Britain can send back to France the illegal migrants caught after crossing the Channel. In return, Britain takes from France the same number of legal migrants — those who applied properly, who have relatives in the UK, or those granted humanitarian status.

On paper it sounds fair. In reality, it looks like a joke. Just fifty people per week. When in fact, on a single day, hundreds attempt the crossing. That is not even a drop in the ocean — it is a drop in an ocean storm.

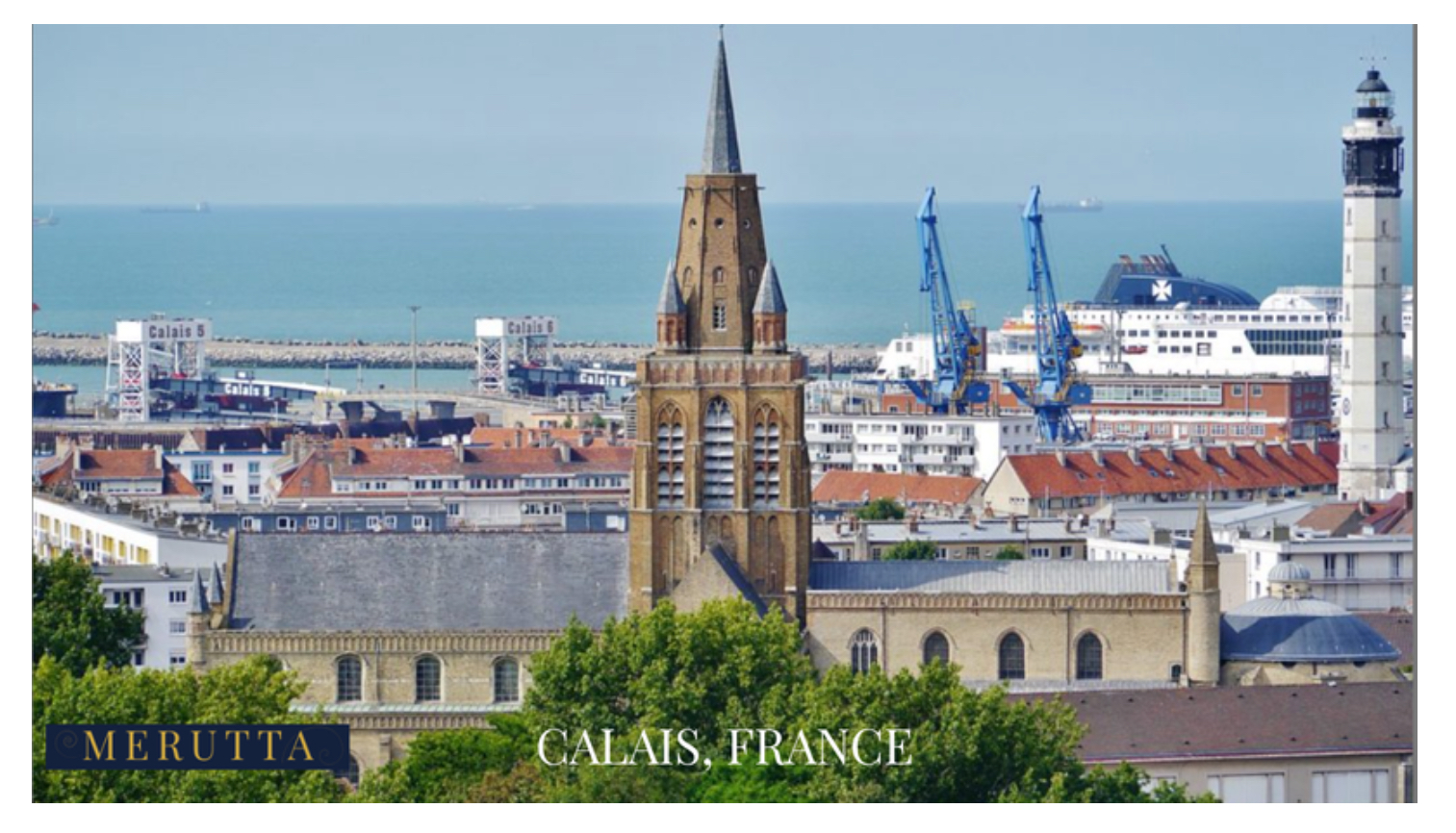

And here comes the main question: who are these people? Where are they from? They are not migrants who already settled in France, received documents, and then decided to leave for Britain. No. These are mostly people without papers, without legal status. They live in makeshift camps around Calais, sometimes right by the beaches.

And here comes the main question: who are these people? Where are they from? They are not migrants who already settled in France, received documents, and then decided to leave for Britain. No. These are mostly people without papers, without legal status. They live in makeshift camps around Calais, sometimes right by the beaches.

Residents are exhausted — and that is why mayor Natacha Bouchart raises the alarm: ordinary life in the city is paralyzed. People cannot even walk to the seafront without passing through groups of migrants who sit and wait for their chance to cross.

Where do they come from? From Africa and the Middle East. Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, Iran. Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia. Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco. They travel thousands of kilometers only to end up on the French coast — waiting for the moment to attempt Britain.

Every night they try to hide in trucks heading to the port. Others climb into flimsy boats, hoping to cross the Channel. Some succeed, many are caught. But many also die. They risk their lives — and the lives of their children. Every crossing is a deadly gamble.

And now, under the new deal, Britain can simply send back those who survived — to France. But here is the real paradox: why send them back to France, and not to their own countries? Why should Paris and London treat France as a permanent reception zone? Why not invest in helping people build their lives at home?

Africa is a continent rich in gold, oil, uranium, diamonds. They have everything needed to develop their countries. And yet millions flee, leaving their lands and families behind. Of course there are wars, corruption, dictators. But the fact remains: Europe spends billions on hosting migrants, while this money could have gone to develop French regions.

And meanwhile, people from Africa who could be the builders of their own nations — doctors, engineers, teachers — leave in search of an easier life in Europe. And here lies the clash. Europe for centuries has lived by values of culture: the Louvre, cathedrals, philosophy, painting, music.

For migrants, the priority is basic survival — work, safety, a future for their children. That is natural. But when such different value systems collide, tension grows. Because these are two worlds that cannot always coexist in harmony.

And then there is what we might call “celebrity charity.” Wealthy stars love to show the world how they are “saving Africa.” They set up a couple of tents with a red cross, invite television crews and reporters eager to film a feel-good story, and announce: “our charity is helping African children get flu shots.” But let’s be honest: one flu shot will not change the fate of an entire continent. That is not a solution.

If each of them built even a single home for a homeless family, one small school with real teachers, one hospital — then Africa would slowly gain roads, education, real opportunities. And then perhaps people would have a choice: to stay at home instead of climbing into rubber boats and risking their lives for the illusion of Europe. But no one does that. Because real work is hard, slow, and does not make glamorous pictures. Beautiful photos bring likes, applause, and new contracts.

And while politicians play with words, and rich stars play at “charity,” Europe faces a reality where northern French cities have become waiting camps. In reality, this is not a solution but a political spectacle. Britain tells its voters: “We are fighting illegals.” France tells its neighbors: “We are cooperating.” But in truth, the flow of migrants does not decrease. They are simply shifted back and forth. As the French president said in July 2025: “The current situation is actually giving an incentive to make the crossing… the British people were sold a lie.”

He meant that Brexit had been sold as a promise to control borders and end illegal migration — but instead Britain faces record crossings and chaos in the Channel. Is France ready to pay for the mistakes of others? Can Europe still balance humanity with security? And if this reality truly becomes the future — what will Europe look like tomorrow?

According to official figures published annually by the French Ministry of the Interior (Ministère de l’Intérieur), France spends between €1.8 and €2.5 billion per year on migrant reception, including housing, healthcare, and integration programmes. In the United Kingdom, the Home Office and the National Audit Office (NAO) regularly report that migration management costs range from £3.5 to £4.7 billion annually, much of it spent on temporary accommodation and asylum processing. Meanwhile, attempts to cross the Channel reached approximately 46,000 in 2024, according to data from the British Border Force.

These numbers are publicly available in official government reports and parliamentary briefings — and they show the true scale of the challenge. Behind the political speeches and symbolic agreements lies a deeper question: not how to move people back and forth across the Channel, but how to address the conditions that make them risk the crossing in the first place.